“Nice surprises” in Dunedin groundwater research

GNS Science experts report “a few nice surprises” after a year of groundwater monitoring – one of the first steps needed to fully understand Dunedin’s vulnerability to sea-level rise and flooding.

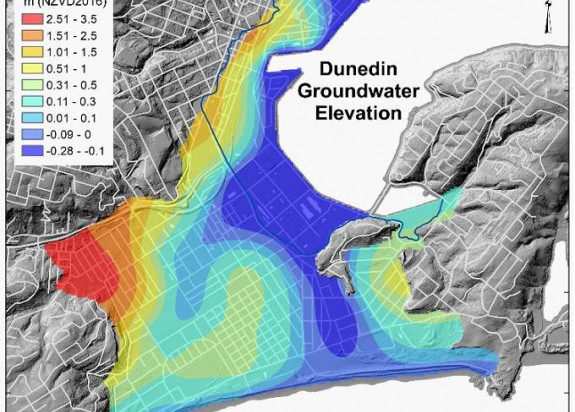

In 2019, Otago Regional Council scientists increased the scale and density of their urban Dunedin groundwater monitoring network from four sites to 23, covering the wider Harbourside-South Dunedin area. The groundwater levels and temperature data has been recorded for a year and is stored in their groundwater database.

Every 15 minutes, automated recorders collect data on how water beneath the city responds to rainfall, seasonal variation, hillslope runoff, pumping and the effect of tides.

“The first year of monitoring has yielded quite a few nice surprises,” Simon Cox, Principal Scientist at GNS Science and the report’s lead author, says.

“Before we started, we heard widespread stories, such as people having to wait for low-tide before digging to get a dry hole in their garden.

“We thought the monitoring would show groundwater is strongly tidal - but in reality, there are very few places where groundwater changes more than 20 mm between low- and high-tide.

“Chemical analyses also indicate saline-rich seawater barely infiltrates more than 800m inland from the sea or harbour.”

The Rise and Fall of Urban Groundwater transcript

The monitoring also indicates that some of the flat low-lying land beneath parts of the city is much less permeable than initially expected.

“Gentle pumping of wells is able to disturb the chemistry of groundwater long after water-levels have recovered, and many places have ‘topsy turvey’ temperatures that are warmest in June and coldest in December,” Dr Cox says.

This suggests water is not moving rapidly through the ground, and that is good news. Further monitoring and analysis needs to continue to improve our understanding of the relationship between present day tides and groundwater levels and the effects of future sea level rise.

South Dunedin Future, a collaborative project between Otago Regional Council and Dunedin City Council are pleased to see these results from the groundwater data being collected.

ORC General Manager Operations, Dr Gavin Palmer says, “Technical staff from both councils will use the analyses presented in this report to help inform the next phase of scientific work, while consulting with the community on potential options to mitigate against natural hazards and climate change impacts through the South Dunedin Future project. Ongoing monitoring and further analyses of the likely effects of climate change on groundwater are still needed to confirm these initial observations based on one year of monitoring only.”

DCC Infrastructure Services General Manager Simon Drew says, “The DCC has budgeted $35 million to spend on flood reduction in the South Dunedin area over the next decade. This new report will form an important part of the technical basis for developing options for exactly how that money will be spent. Monitoring observations are available for free download here.

“We look forward to further collaboration with the Otago Regional Council, GNS Science, the community and others as we work towards safely adapting to the effects of climate change.”

Dunedin groundwater is monitored by Otago Regional Council and GNS Science, with chemical analyses completed by University of Otago. The city is seen as a test case for developing methods to monitor, map, model and help mitigate the effects of rising groundwater and sea-level rise. This research forms part of the NZSeaRise Endeavour Programme(external link) funded by MBIE(external link).

The baseline data presented in the report are accessible through contacting ORC, who maintain the Dunedin groundwater database along with rainfall and river levels.