The latest on Whakaari/White Island

GNS scientists are actively monitoring Whakaari/White Island which sits 48 km offshore from Whakatane and has been at Volcanic Alert Level 3 since 9 August. Read on for the latest news, and answers to some frequently asked questions.

The Volcanic Alert Level (VAL) for Whakaari was raised to VAL3 on 9 August 2024 when satellite images obtained by NZ MetService indicated an increase in the amount of volcanic ash in the plume. This suggested that some form of minor eruption had occurred.

Since then, the volcano has experienced a period of near continuous minor eruptive activity with variable but minor amounts of volcanic ash in the steam and gas plume. This could continue for some time (weeks to months).

Our local web cameras and observers of the volcano will see this low-level volcanic activity as discoloration of the plumes, as they now contain minor amounts of volcanic ash. The local winds will usually blow the plume over and away from the island. Under calm conditions the plume may also stand up above the island and under ideal conditions can reach 1-2 kilometres high.

Our latest gas flight (14 August)(external link) confirmed an increase in the amount of volcanic gas being emitted from the volcano and the presence of a minor amount of volcanic ash in the plume, being transported by the wind. The ash comes from a new active vent about 10-15 m across and all available information confirm a change in the eruptive activity from the island since the beginning of August.

So, what does this mean?

We are currently observing intermittent minor eruptive activity, with the hazards largely restricted to the island. This is part of the typical eruptive cycles seen at Whakaari/White Island. Based on eruptive episodes over the past 48 years, this activity could continue for some time, weeks to months.

The unrest over the last 6 weeks, including the current minor volcanic activity, is driven by moderate-to-high temperature gas and steam venting to the surface from the magma at depth. The hot gas is from the magma beneath the volcano. As the magma is now shallower it can cause higher temperature gas to vent and increase the gas volumes, which will likely continue to drive ongoing eruptive activity, like what is happening now.

As the weather changes the plume may at times be blown towards the Bay of Plenty coast. However, with the current levels of ash emission, there is a very low likelihood of ash impacting the mainland. The steam and gas component may become noticeable. The most likely, though infrequent, impact of a steam and gas plume is that people might smell volcanic gas and possibly find it an irritant to the eyes and respiratory system (see link to Health information below). The level of volcanic activity would have to change significantly for this likelihood to increase.

Ash emission views from our Te Kaha and Whakatane cameras. Ash is seen falling from the downwind part of the plume near the volcano to the left (west) of the main plume.

We do not expect ashfall on the mainland with the current state of activity. The ash created by the current activity is producing very small particles (smaller than the width of human hair) and typically they do not fall to the ground. Larger particles do fall near the volcano – however, the smaller ones remain suspended in the air drifting off down wind.

Should the volcanic activity increase, people would be provided with appropriate advice to manage any hazard effects (see links below for more information). If required based on volcanic activity, GNS provides ashfall forecast maps via Volcanic Activity Bulletins(external link).

Where to go to for advice

For information and advice about the impacts of the steam and gas plume or volcanic ash, should it reach the coast visit the following agency websites:

BOP Emergency Management site(external link)

Health New Zealand(external link)

Has this happened before?

Our history of the volcano shows there was intermittent, short–lived eruptive activity that did not impact the onshore environment from around 1820 to 1976. Then from 1976 to 2000 a period of enhanced activity occurred; the activity during this period was sometimes 3 to 5 times larger than the present activity.

Occasionally the steam and gas plume and/or ash cloud reached the coast, but usually went unnoticed. As with the activity now, the ash particles were very small in size and generally only fell from the plume near the volcano. Further activity has occurred in 2012-13, 2016 and 2019. All impacts were restricted to the island area.

Frequently asked questions on the recent activity at Whakaari/White Island

Q: How deep is the magma under Whakaari?

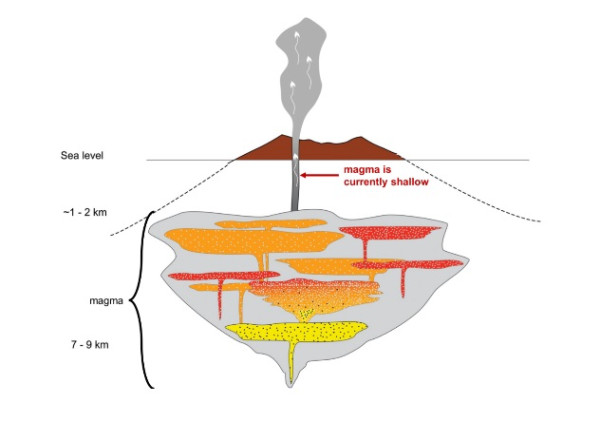

The volcanic unrest that is normally present at Whakaari/White Island is typically driven by magma at a few kilometres' depth (2-9km). So, magma is nearly always present under the volcano, as shown in the diagram below. When some of this magma moves to shallower depths (0.5 to 2 km) the level of activity increases.

Q: Is the saying true that “when white island constantly vents, it is a good thing as the pressure is being released so it wouldn't erupt, and that we should be more concerned if it stops doing that”?

This is a great urban myth that has been part of the New Zealand culture for years. The origin is most likely a newspaper article from as far back as 1864, where a letter was published from a disgruntled MP who was objecting to Parliament moving from Auckland to earthquake-prone Wellington. The MP referred to White Island as ‘The great safety valve against earthquakes in Auckland,’ justifying his opinion that Auckland had lower risk of an earthquake.

The truth is that our active volcanoes behave independently from one another and are not connected underground. And we must remember that Whakaari/White Island is an active volcano and has the potential to erupt with little or no warning when in a state of minor volcanic unrest.

Q: Could a big eruption cause a tsunami?

Island volcanoes and submarine volcanoes can potentially produce a ‘volcanic tsunami.’ However, there is nothing in the historic and geological records to indicate this has ever happened at Whakaari/White Island.

The GNS-led Beneath the Waves programme(external link) is currently investigating the potential for the Whakaari and Tūhua volcanoes to trigger a tsunami, and other volcanic hazards, and assess the impacts these could have on the surrounding area.

Q: Are recent earthquakes related to the volcanic activity?

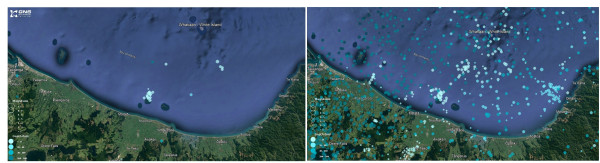

Clusters of small earthquakes between Whakaari/White Island and the Bay of Plenty Coast are quite common, as many faults exist in the eastern Bay of Plenty and extend offshore. In the last 12 months, we have located 114 earthquakes in the same area as the earthquakes last week. We consider these recent quakes to be caused by regional faulting, rather than related to the volcano. We do see larger earthquakes related to the plate boundary processes at East Cape, in the Whakaari/White Island area, but these are usually deeper than 30-40 km.

We do see distinct types of earthquakes, including those related to tectonic (faulting) and those related to volcano processes. So, when we analyse the earthquakes, we can see that the recent earthquakes are tectonic and not volcanic.

Q: How do we monitor Whakaari/White Island?

Our team of experts are keeping watch as part of their roles in the Volcano Monitoring Group, and we have the National Geohazards Monitoring Centre, which provide around-the-clock monitoring services.

Our experts are drawing on a toolkit that includes monitoring stations on the mainland, observation and gas flights, and remote sensing technology (like gas and thermal satellite imagery). We also receive information about Whakaari from satellite data from the German and European Space Agencies, which can provide us a view of ground deformation and gas emissions.

All the information we receive through those channels is complemented with data from the Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC) at NZ MetService. These data can confirm if larger ash producing eruptions have occurred, via satellite remote sensing and rain radar data.

We will have more detail on our remote monitoring in a story later this week.

Q: When will you put more cameras on the island / Are you ever going to be able to get your monitoring gear on the island up & running again?

Currently we are unable to access Whakaari, which means we have been unable to service or replace our monitoring equipment. GNS is working alongside NEMA, Ministry of Transport and Civil Aviation Authority, to mitigate the risk of our reduced monitoring service on Whakaari/White Island and understand future monitoring requirements. In the meantime, we are planning the design and installation of a future network of seismo-acoustic monitoring stations, GPS, gas-measuring instruments, and cameras that would enable us to establish real-time, on-island monitoring, when and if that is required.

GNS Science’s Volcano Monitoring Group (VMG) with the help of the NZ Metservice Volcanic Ash Advisory Centre (VAAC), and the National Geohazards Monitoring Centre, will continue to closely monitor Whakaari/White Island for further changes in unrest.